Even the word immunity creates confusion. When immunologists use it, they simply mean that the immune system has responded to a pathogen—for example, by producing antibodies or mustering defensive cells. When everyone else uses the term, they mean (and hope) that they are protected from infection—that they are immune. But, annoyingly, an immune response doesn’t necessarily provide immunity in this colloquial sense. It all depends on how effective, numerous, and durable those antibodies and cells are.

From the September 2020 issue: How the pandemic defeated America

Immunity, then, is usually a matter of degrees, not absolutes. And it lies at the heart of many of the COVID-19 pandemic’s biggest questions. Why do some people become extremely ill and others don’t? Can infected people ever be sickened by the same virus again? How will the pandemic play out over the next months and years? Will vaccination work?

To answer these questions, we must first understand how the immune system reacts to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. Which is unfortunate because, you see, the immune system is very complicated.

It works, roughly, like this.

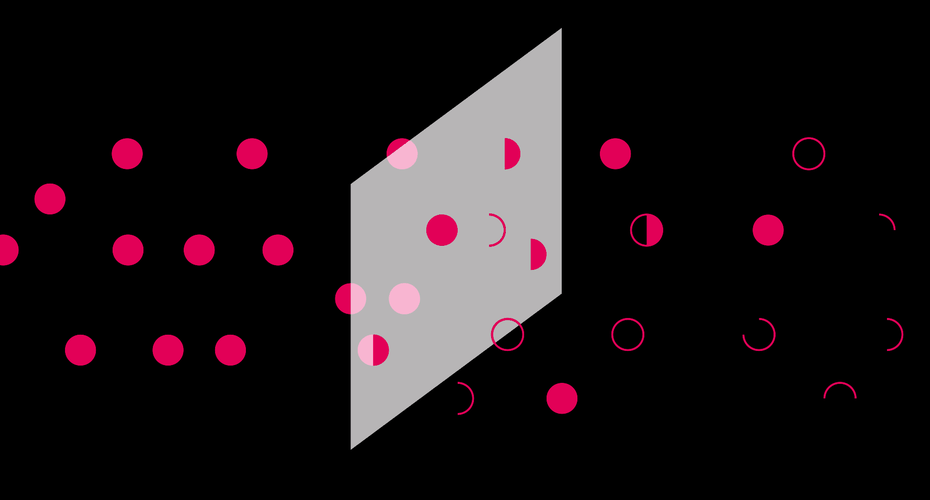

The first of three phases involves detecting a threat, summoning help, and launching the counterattack. It begins as soon as a virus drifts into your airways, and infiltrates the cells that line them.

When cells sense molecules common to pathogens and uncommon to humans, they produce proteins called cytokines. Some act like alarms, summoning and activating a diverse squad of white blood cells that go to town on the intruding viruses—swallowing and digesting them, bombarding them with destructive chemicals, and releasing yet more cytokines. Some also directly prevent viruses from reproducing (and are delightfully called interferons). These aggressive acts lead to inflammation. Redness, heat, swelling, soreness—these are all signs of the immune system working as intended.

Read: Why some people get sicker than others

This initial set of events is part of what’s called the innate immune system. It’s quick, occurring within minutes of the virus’s entry. It’s ancient, using components that are shared among most animals. It’s generic, acting in much the same way in everyone. And it’s broad, lashing out at anything that seems both nonhuman and dangerous, without much caring about which specific pathogen is afoot. What the innate immune system lacks in precision, it makes up for in speed. Its job is to shut down an infection as soon as possible. Failing that, it buys time for the second phase of the immune response: bringing in the specialists.

Amid all the fighting in your airways, messenger cells grab small fragments of virus and carry these to the lymph nodes, where highly specialized white blood cells—T-cells—are waiting. The T-cells are selective and preprogrammed defenders. Each is built a little differently, and comes ready-made to attack just a few of the zillion pathogens that could possibly exist. For any new virus, you probably have a T-cell somewhere that could theoretically fight it. Your body just has to find and mobilize that cell. Picture the lymph nodes as bars full of grizzled T-cell mercenaries, each of which has just one type of target they’re prepared to fight. The messenger cell bursts in with a grainy photo, showing it to each mercenary in turn, asking: Is this your guy? When a match is found, the relevant merc arms up and clones itself into an entire battalion, which marches off to the airways.

Source: The Pandemic’s Biggest Mystery Is Our Own Immune System – The Atlantic